On the zeitgeist

thoughts on a time when the Internet was sexy

I’ve been thinking about the concept of the zeitgeist a lot because of a particularly tormenting conversation I’ve had to have multiple times over the past year: explaining the phrase “Y2K” to someone younger than me.

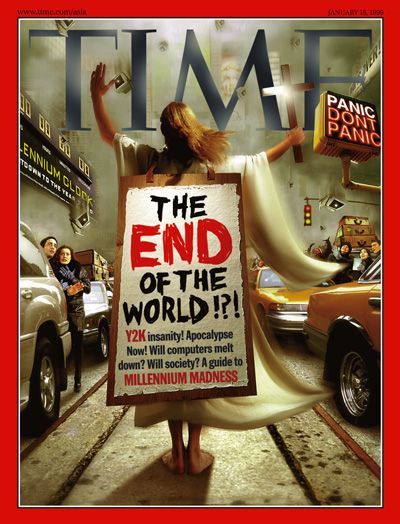

I know that I am aging like any human does, and time only goes one way and that’s forward, and BuzzFeed has stopped producing lists to make 90’s kids feel old and is now in the business of making Gen Z feel old. I’m not in denial here. And yet, this one issue stings. Perhaps it is because I am particularly obsessed with Y2K and I am attempting to project my own feelings of its importance onto others. But I think it’s because the concept of Y2K — the turn of the millennium, the possible shutdown of all technology, the wild feeling that the future was here and we were all gonna live in space soon — loomed so gigantic in the public consciousness. EVERYONE cared about Y2K, children! It was a whole THING! But such is the way of the zeitgeist. In 20 years, some 28-year-old will make a joke about “fake news” to a 23-year-old and get the same blank stares I receive when I mention Y2K. “Fake news!” the elder twentysomething will repeat. “You know? The president said it like, every day for 4 years? It was a joke, like when you didn’t want to believe something? FAKE NEWS?” but the other member of the conversation will politely shake their head and point out that they may have been too young to know about that.

A zeitgeist is a strange thing to try to analyze as it’s happening, though you can of course observe what’s going on. Take 2012, for instance. It was the middle of the Obama years, a few years out of the Great Recession, and the pop music on the charts was the sugariest kind of bubblegum — “Call Me Maybe,” “Starships,” “We Are Never Getting Back Together,” “Moves Like Jagger.” Shit would get dark again soon enough. 2014 would see Gamergate, the ugly online hate campaign that led to today’s Nightmare Internet, and the Ferguson uprising after Mike Brown’s murder. 2016, of course, was such an unrelenting pile-on of bad news that it felt like the actual apocalypse. But in 2012, the apocalypse was a joke. The Mayans had predicted the world would end in the second half of December, giving us a full year to ironically reference it with the reassurance that no one really believed it. In that pocket of time after the financial crash and before the predicted apocalypse, it even hit our pop music. Usher urged us to “Dance, dance like it’s the last, last night of your life” and “Keep downing drinks like there is no tomorrow.” Ne-Yo jumped on a Pitbull track to beg us to “Give me everything tonight / For all we know, we might not get tomorrow.” Kesha implored us to “make the most of the night like we’re gonna die young.” Removed from the context of the Mayan prediction, it seems like a strange coincidence, multiple pop stars using the world ending as a goofy shorthand for partying. But it was just a dumb phenomenon on everyone’s mind that trickled into our pop culture and spread even further.

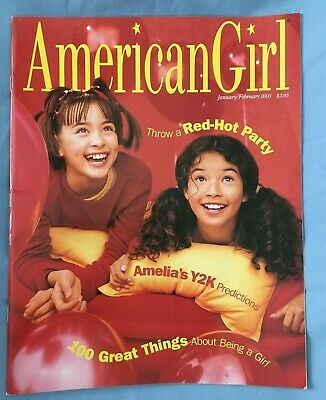

The problem with explaining the zeitgeist to someone who didn’t live through it is that you can’t. One has to live through a particular pop culture phenomenon to understand it. Two of my maddening conversations with The Youth have started as discussions about fashion. In one, a 23-year-old showed me a bubbly silver purse she was contemplating buying, and in the other, a 22-year-old showed me some baby blue sunglasses. In both cases, I responded that the look was very Y2K. A valid point, I think! Y2K had its own aesthetic! Computer animation was in its fledgling state, the entire earth was preoccupied with the impact of the new millennium on technology, and a booming economy made consumerism stupid and fun. And so we got all kinds of wild clothes, and now they’re coming back in style, and the kids don’t even get it. They don’t even know why.

Which is fine. Of course it’s fine! I was born in 1991 and in any given week will dress like it’s the 40s, 60s and 80s on different days, so I certainly have no room to complain about decade appropriation or whatever. What has upset me so much about this whole thing is the realization that a concept that was on everyone’s mind has vanished from the collective consciousness. It felt important, but it wasn’t. Most of the Youths I have surveyed on this issue are vaguely aware of “the Y2K problem,” the fear that the changing dates would screw up a bunch of tech, but don’t know the phrase “Y2K” itself. We used it to describe an entire year, a moment in time, and that moment has passed. I thought that the term was historical, something that would be preserved. But in the end, I guess it’s all just pop culture.

Y2K was an exceptionally stupid time in a lot of ways. I owned three physical CDs from three different artists with sexy pop songs about the World Wide Web.

Yes, I owned the Eiffel 65 album — they were known for their song “Blue (Da Ba Dee)” which is a thing that charted because like I said, it was a stupid time. You’re more than forgiven if you have forgotten their name. Anyway, it had a song that featured the following lyrics:

I want a click, a click to your heart

A hyperlink into you

A sexual browser from here to the end

A newsgroup one on one

Don’t need a modem to connect to your mind

No search engine to find you

I want a click, a click to your heart

A hyperlink to go inside you

I guess what I’m saying is there’s absolutely no reason for me to get precious about Y2K. I’m sad that The Kids These Days didn’t get to experience a world when everything was bright and colorful and dumb and the economy was solid and the country wasn’t at war, but it’s cool that pop stars are allowed to say they’re feminist and appear in public if they’re not a size 00 now, which is more than we could say for our celebrities back then. I hope the teens enjoy their vintage rhinestoned jeans and colored sunglasses, and that it offers them some respite from panicking about school shootings and climate change. Perhaps if we all get our shit together and clean up the planet, we can one day experience another goofy, fun era. It seems impossible to imagine now, but like all zeitgeists, this too shall pass.